GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – December 2017

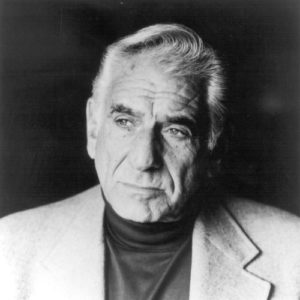

It was in December 1989 – a staggering 28 years ago – that Gramophone put me and Leonard Bernstein in the same room together. It was an extraordinary hour, the details of which I shall never forget and indeed have now chosen to enshrine in a cabaret-like entertainment – Bernstein Revealed – which will kick-off the Centenary of his birth as part of the Barbican’s Total Immersion weekend next month. 2018 is going to be a year full of Bernstein – the music, the man, the ethos.

It was in December 1989 – a staggering 28 years ago – that Gramophone put me and Leonard Bernstein in the same room together. It was an extraordinary hour, the details of which I shall never forget and indeed have now chosen to enshrine in a cabaret-like entertainment – Bernstein Revealed – which will kick-off the Centenary of his birth as part of the Barbican’s Total Immersion weekend next month. 2018 is going to be a year full of Bernstein – the music, the man, the ethos.

For me personally it was always Bernstein’s ability to embrace music in all its manifold guises that I found real kinship with. He had a nose for theatre, which I shared, he adored genre-hopping, which I totally related to, and he composed as he conducted – in the moment. I still maintain that Mass – his theatre piece for Singers, Players and Dancers – is his most important work. Not just on account of its virtuosity and the brilliant “gamesmanship” of its composition but because it demonstrates how music can transcend all the social, political and religious barriers imposed upon it. In other words, if you are truly musical then the joy lies not in what separates us but what unites us. Those who find Mass tasteless or cheesy or even embarrassing in its myriad juxtapositions of style – like Bernstein himself the piece wants, needs, to experience it all – should perhaps be examining their musical inhibitions and the reasons for them. Mass should be liberating. That’s what Bernstein, the man, the musician, the composer, personified.

It wasn’t easy for him. When Gramophone confirmed a cover feature interview tied to the new recording of his bountiful quasi-operetta Candide I resolved to focus only on Bernstein, the composer. In the event it was the right decision – and certainly the surest way to his heart. Because what was so startling – and so touching – about that interview was how candidly he acknowledged the hurt that so many of his musical contemporaries didn’t take him seriously as a composer. Could it be that this misplaced insecurity was at the root of his attempts to “elevate” glorious theatre works like West Side Story and Candide to be what they were not, casting them inappropriately and inflating them to the point where something as glorious as “Make Our Garden Grow” from Candide aspired (why?) to be Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony?

It is well chronicled what Bernstein explored ways in which he could be more “cutting edge” (whatever that means) as a composer – but the realisation was always there that he could only really be himself. And with such great gifts (not least as a melodist, that dying art) why would he want to be otherwise? The irony is that had he lived just a few more years he would have seen terrific works like his Serenade for violin, strings and percussion and Symphony No 2 ‘Age of Anxiety’ enter the core repertoire. Both those works memorably use variational techniques to affect a sense of constant evolution. So how poetic that 27 years after his death we effectively experience a succession of new beginnings every time we hear them.

You May Also Like

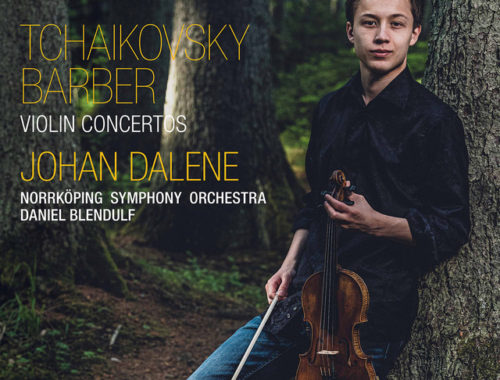

GRAMOPHONE Review: Barber / Tchaikovsky Violin Concertos – Johan Dalene, Norrköping Symphony Orchestra/Blendulf

26/02/2020

GRAMOPHONE Review: Songplay – Joyce DiDonato

27/03/2019