Candide, Menier Chocolate Factory

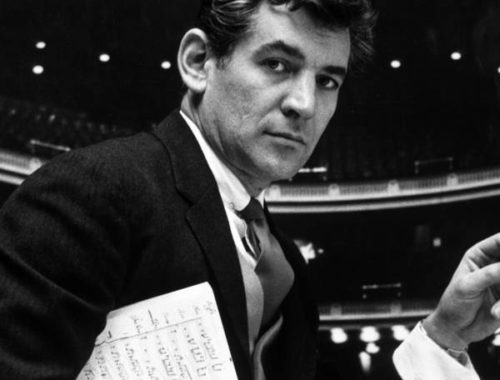

It’s one of theatre’s great ironies that turning Volaire’s bitter satire Candide into a musical proved every bit as taxing and fraught with disaster as the journey to a better life endured by the novella’s principal characters. But through all the rewrites and rewrites of rewrites that came off the back of Lillian Hellman’s cumbersome and unworkable book there was Leonard Bernstein’s bountiful score – one of the richest, wittiest, and sheerly inventive in all musical theatre. Bernstein wrote more music for Candide than for any other Broadway enterprise and even in its completest form, as here at the Menier Chocolate Factory, there are omissions. You can familiarise yourselves with those in Bernstein’s eleventh-hour recording with the London Symphony Orchestra – though nothing could really be further from the spirit of this madcap piece than the inflated grandiosity of that recording. Bernstein never could give himself a break from pursuing the great American opera – even when writing the greatest of all possible musicals. Just imagine he worked on Candide and West Side Story concurrently.

It’s one of theatre’s great ironies that turning Volaire’s bitter satire Candide into a musical proved every bit as taxing and fraught with disaster as the journey to a better life endured by the novella’s principal characters. But through all the rewrites and rewrites of rewrites that came off the back of Lillian Hellman’s cumbersome and unworkable book there was Leonard Bernstein’s bountiful score – one of the richest, wittiest, and sheerly inventive in all musical theatre. Bernstein wrote more music for Candide than for any other Broadway enterprise and even in its completest form, as here at the Menier Chocolate Factory, there are omissions. You can familiarise yourselves with those in Bernstein’s eleventh-hour recording with the London Symphony Orchestra – though nothing could really be further from the spirit of this madcap piece than the inflated grandiosity of that recording. Bernstein never could give himself a break from pursuing the great American opera – even when writing the greatest of all possible musicals. Just imagine he worked on Candide and West Side Story concurrently.

So here at the Chocolate Factory Candide is cut down to size, its cast of thousands traversing the globe as a troupe of traveling players, its orchestra (under the direction of Seann Alderking) a characterful 9-piece with Jason Carr’s clever orchestrations popping our ears with their ingenuity as treble recorder and accordion (what an inspired idea) suggest period and “locality” and streetwise earthiness whilst not compromising the sweep and super-romanticism of the ballads. The catchiness of the score is unrivaled in Broadway history with Bernstein trumping his Gilbert and Sullivan favourites and their Viennese equivalents in a confection as sweet as it is cynical. To have matched Voltaire in this respect is one of the score’s enduring triumphs and I don’t know of any sequence in a musical more savagely comic (or more insanely silly) than the Auto-da-fé number. Hats off to David Charles Abell’s musical supervision, this talented company (choc-full of terrific voices) really nailed it, if you’ll forgive the metaphor.

Director Matthew White and choreographer Adam Cooper understand that nothing less than breathless pacing can bring this piece alive and the unseemly haste with which they spirit us through the global itinerary would put even Thomas Cook to shame. Multiple narrators and improvised props is definitely the way to go here – notwithstanding the recurrent feeling that we’ve been here before – and we the audience are now very much at the fully participating centre of the action conveniently “on the spot” where an extra pair of hands or an incidental player might urgently be required.

Our unlikely hero and heroine – Candide and Cunegonde – look and sound perfect, Fra Fee sweetly attending the score’s moments of tenorial contemplation and repose most touchingly and really getting to the heart of his “aria of disillusionment”, “Nothing More Than This”, which Bernstein thought of as his Puccini aria and which the original producers of the show believed would hold up the arrival of the finale and unbelievably insisted upon ditching.

As Cunegonde Scarlett Strallen proves the revelation of the evening negotiating her stratospheric soprano coloratura with astonishing aplomb and better yet totally understanding the orgasmic lust of Bernstein’s Gounod’s Faust “Jewel Song” parody “Glitter and Be Gay” where diamonds are not just a girl’s best friend but her ONLY friend. A reminder, too, of what a great contribution to this score lyricist Richard Wilbur made.

Casting doesn’t falter here and one should applaud Jackie Clune’s wonderfully ripe, raped and pillaged Old Lady, James Dreyfus’ indestructible Pangloss (and Cacambo and Martin), and the ringing tenor of Ben Lewis at the service of his gallery of villains.

There’s always the clinching moment of catharsis in Bernstein scores and the mother of them all is “Make Our Garden Grow” where even Voltaire’s scepticism pales beneath the wholehearted belief of the melody. When the ensemble goes a capella at the climax there isn’t a soul alive who’s not going to know from the shiver down their spine that they are in the presence of greatness.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE Review: Mahler Symphony No. 6 – MusicAeterna/Currentzis

02/01/2019

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – August 2018

15/08/2018