Floyd Collins, Wilton’s Music Hall

It’s one of those true stories you really couldn’t make up. In 1920s Kentucky, Floyd Collins, visionary cave explorer, happens across a spectacular sand cave – the sand cave of his dreams – only to become trapped on his way back to the surface. The media attention he might have hoped would turn his discovery into a commercial proposition for him and his impoverished family is instead – irony of ironies – focused on his entrapment. Will he/won’t he make it back to the light. While the carnival arrives above ground, Floyd’s dark night of the soul is played out below. Billy Wilder turned it into a rather good movie, Ace in the Hole, but it was never on the face of it the stuff of which musicals are made.

It’s one of those true stories you really couldn’t make up. In 1920s Kentucky, Floyd Collins, visionary cave explorer, happens across a spectacular sand cave – the sand cave of his dreams – only to become trapped on his way back to the surface. The media attention he might have hoped would turn his discovery into a commercial proposition for him and his impoverished family is instead – irony of ironies – focused on his entrapment. Will he/won’t he make it back to the light. While the carnival arrives above ground, Floyd’s dark night of the soul is played out below. Billy Wilder turned it into a rather good movie, Ace in the Hole, but it was never on the face of it the stuff of which musicals are made.

Well, not until composer/lyricist Adam Guettel and book writer Tina Landau took it to heart. Guettel’s extraordinary gifts may or may not be directly related to his distinguished heritage but the odds of inheriting the “genius gene” rise exponentially when your grandfather is the great Richard Rodgers. Guettel is not prolific – indeed frustratingly quite the reverse. But his two produced theatre pieces (three if you count the extraordinary song-cycle Myths and Hymns which does get staged) – Floyd Collins and The Light in the Piazza – are both unquestionably masterpieces of the genre and it is tempting to presume that new work waiting, as it were, in the wings will not see the light of day until it too is honed to such a status.

Floyd and Piazza inhabit different universes, musically speaking, but they are so clearly by the same composer. Guettel’s voice – his searching melodic lines (he prefers to journey than to arrive), wavering as they do between key centres – are uniquely his own. The beauty of Floyd Collins is in its complexity – and yet the Bluegrass tone and homespun directness of the musical language sounds on the surface of it thoroughly authentic. You almost don’t notice that it is dicing with atonality and that the band (MD Tom Brady) seems to have cross-fertilised its country accenting with that of Stravinsky.

Guettel miraculously writes the haunting cave echoes into the yodelling scat of Floyd’s vocal lines. And there’s even a nod to the city slicking close harmony groups of the 1920s when Guettel wittily gives the stage to a quartet of reporters whose talent for misinformation knows no bounds.

But the genius of Floyd Collins lies with its intimacy, with those quiet moments where Floyd (the excellent Ashley Robinson), his brother Homer (Samuel Thomas), and sister Nellie (wonderful Rebecca Trehearn) reflect in isolation or in concert. One of the joys of Jonathan Butterell’s terrific revival in the still mystical space that is Wilton’s Music Hall (whose aged dustiness, weathered facade, and hollow acoustic – occasionally obtrusive to clarity – is generally so welcoming of the piece) is the way in which his pitch-perfect cast inhabit the style of the score. Rebecca Trehearn so perfectly catches the telling vocal aches and breaks and sobs of her numbers while Ashley Robinson and Samuel Thomas make something truly brilliant of the sensational act one closer “The Riddle Song” (why no song or cast list in the programme?).

This is one of the most exhilarating moments in contemporary musical theatre (Sondheim is documented as saying he wished he’d written it) as Floyd suddenly imagines he is free and reliving childhood games with his big brother. It’s a device which will reoccur at the climax of the piece where the imaginary “Grand Opening” of the Great Sand Cave assumes, in Butterell’s staging, an almost religious pageant-like quality with the entire Collins family attired in their Sunday best. But suddenly the cave echo fails to return Floyd’s jubilant vocalise and he is alone again.

There’s an eleven o’clock number “How Glory Goes” in which Ashley Robinson duly breaks your heart but by then the show is no longer happening on the Calvary-like scaffolding on which Floyd is in a sense crucified but in our heads and hearts. That’s the genius of Guettel and the simple truth of this production.

You May Also Like

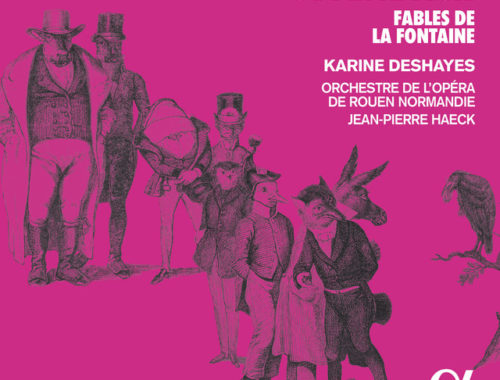

GRAMOPHONE Review: Offenbach Six Fables de La Fontaine – Karine Deshayes, Orchestre de l’Opéra de Rouen Normandie/Haeck

29/01/2020

GRAMOPHONE Review: Bruch Violin Concerto No 1, Price Violin Concertos 1 & 2 – Randall Goosby, Philadelphia Orchestra/Nézet-Séguin

27/06/2023