GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – December 2018

The recent revival of The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess at English National Opera and the prospect of comparing all its available recordings in BBC Radio 3’s Record Review early next year has prompted me to look a little deeper into this landmark score and to reassess its significance in the chronology of American music theatre. Along with West Side Story it remains the score that the great and the good of the genre wish they had written. There is a stratospheric level of ambition about Porgy and Bess, an urgent need to push the American musical, opera, call it what you will, to new heights, to reconcile an indigenous folksiness to high sophistication.

The recent revival of The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess at English National Opera and the prospect of comparing all its available recordings in BBC Radio 3’s Record Review early next year has prompted me to look a little deeper into this landmark score and to reassess its significance in the chronology of American music theatre. Along with West Side Story it remains the score that the great and the good of the genre wish they had written. There is a stratospheric level of ambition about Porgy and Bess, an urgent need to push the American musical, opera, call it what you will, to new heights, to reconcile an indigenous folksiness to high sophistication.

Stephen Sondheim (one of those who would happily put his name to it) cites the lyric of its opening number – the bluesily pentatonic ‘Summertime’ (a melody it has been suggested is redolent, too, of a Ukranian Yiddish lullaby) – as the key to establishing the tone of the entire piece. The first line of that lyric hangs on one word: ‘and’. ‘Summertime and the livin’ is easy’. The obvious (and more boringly literate) choice would be ‘Summertime when the livin’ is easy’. But the lyricist’s ‘and’ lends a poetic immediacy to the song. It adds an air of the colloquial and personal to Clara’s languid lullaby. In other words, this ‘community’ has its own special way of expressing the loftiest emotions.

‘Community’ is another key contributor to the evolution and success of the piece. It is that which makes it so organic. The great set-pieces – Robbins’ Wake, the Picnic, the Storm (how astonishing is that six-part improvisatory passage at its close) – are its emotional climacterics. When he was writing the score Gershwin cited Wagner’s Die Meistersinger as one source of inspiration to him. Clearly it had not eluded him that Wagner’s success lay in identifying his ‘community’ individually and collectively. And that’s exactly what Gershwin does in Porgy and Bess. Plus everything about the piece is symphonically unified from a network or Wagner-like leitmotifs. They carry the emotional memory of the piece forward, they bind the orchestral and vocal elements. The last thing you hear as Porgy sets off on his impossible quest to find Bess at the close of the opera is Porgy’s theme conjoined with ‘Bess, You Is My Woman Now’. It’s Tristan und Isolde all over again – two souls reunited in death.

So why is Porgy and Bess so rarely staged? It has very particular demands – of course, it does – but could it also be that its challenges are not entirely compatible with its hit ‘songs’ in the public’s imagination. Both Broadway and the West End attempted to reinvent it as a book-song musical, retaining the ‘numbers’ but stripping away much of the through-sung superstructure and replacing it with dialogue. What a betrayal of Gershwin’s achievement.

But alas, it’s a sign of our times. Never mind the context, give us the great songs. The conductor of the latest ENO revival was John Wilson – established champion of Broadway and Hollywood fare – but I think there is little doubt that the enthusiastic audiences for his ‘greatest hits’ concerts up and down the land would always favour the compilation format over complete shows. We can only hope that in the case of Porgy and Bess diversity will finally win the day for this enduring masterpiece.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE Review: Bartók Concerto for Orchestra/Music for Strings, Percussion & Celesta – Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra/Mälkki

10/01/2022

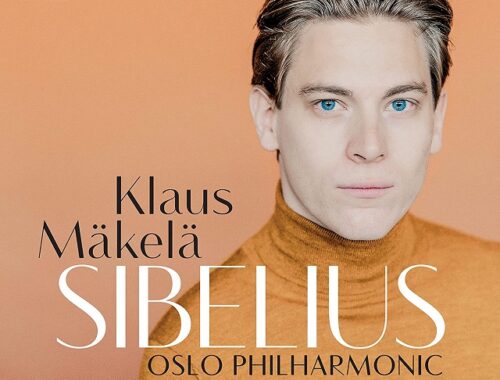

GRAMOPHONE Review: Sibelius Complete Symphonies – Oslo Philharmonic/Makelä

25/04/2022