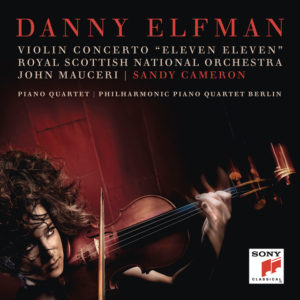

GRAMOPHONE Review: Elfman Violin Concerto ‘Eleven Eleven’ – Cameron, Royal Scottish National Orchestra/Mauceri

In his liner note introduction to these stand-alone concert works Danny Elfman asks the question so often asked, namely why it is that audiences for movie music and classical music concerts are so markedly different when from a musical standpoint the two worlds coexist in so many ways? The answer, I feel sure, lies with ‘associations’. Movie music fanatics are collectors at heart and at the root of their enthusiasm is the inescapable fact that they have something to hang their favourite scores on: an overriding narrative but equally specific scenes, images, moments. And the cues are generally shorter, pithier, less demanding than music developing in the abstract over longer spans.

In his liner note introduction to these stand-alone concert works Danny Elfman asks the question so often asked, namely why it is that audiences for movie music and classical music concerts are so markedly different when from a musical standpoint the two worlds coexist in so many ways? The answer, I feel sure, lies with ‘associations’. Movie music fanatics are collectors at heart and at the root of their enthusiasm is the inescapable fact that they have something to hang their favourite scores on: an overriding narrative but equally specific scenes, images, moments. And the cues are generally shorter, pithier, less demanding than music developing in the abstract over longer spans.

Elfman is probably best known for his collaborations with the freaky talent that is Tim Burton. They are a supremely effective double-act, a meeting of minds, sensibilities, and eccentricities that make them a perfect fit. Indeed, some of the capriciousness that makes Elfman chime so completely with Burton rubs off here. Mostly, though, these accomplished and entertaining pieces owe a lot (as do so many movie scores) to Elfman’s self-confessed passion not just for the romantic classical repertoire as a whole but specifically for the 20th century Russians.

Shostakovich and Prokoviev loom large in the Violin Concerto ‘Eleven Eleven’. There is a distinctly Shostakovian sensibility in the inky lyricism of the opening bars, the bass line brooding over the second idea as the soloist spins arpeggios above. And then we’re off into the Animato hand-in-hand with Prokofiev whose spiky mordant humour has much in common with Burton. Indeed they behave like distant cousins.

Elfman gives his soloist Sandy Cameron plenty to exercise her (they first collaborated on the Cirque du Soleil show Iris) and the solo writing – not least in the cadenzas (gate-crashed in the motor second movement by the percussion section) – is propulsive and exhilarating. On the flip side of the coin is the darkly lyric minimalism of Shostakovich and I like the composerly way in which Elfman has the soloist emerge from the string oration at the start of the third movement Fantasma (there’s a movie-derived title if ever there was one) the 4-note idea hooking us like the best film cues do.

I wouldn’t want to imply that what Elfman is doing here is writing movie music in all but name – not at all. But I would say that the development within the piece feels motivated by arbitrary changes of mood – as in ‘what next?’ – rather than something more organic. That said, the ‘trip’ is full of incident and the exhilarating climax of the finale shows his prowess and relish for the big gesture but also a deeper instinct by resisting the big finish and returning to the lachrymose beginnings of the piece.

In some ways the Piano Quartet (written at the request of players from the Berlin Philharmonic – now there’s a compliment) feels more like a concert piece in a movie-free zone. Elfman’s restless nature is still pervasive – indeed it sometimes feels like a latter-day kind of kinderszenen with the sinister games of the second movement (‘Kinderspott’) typifying the child in Elfman. Sometimes I wish his music would just settle in one place and simply evolve. Paradoxically the shortest movement ‘Ruhe’ (1’ 40”) does just that – in microcosm.

You May Also Like

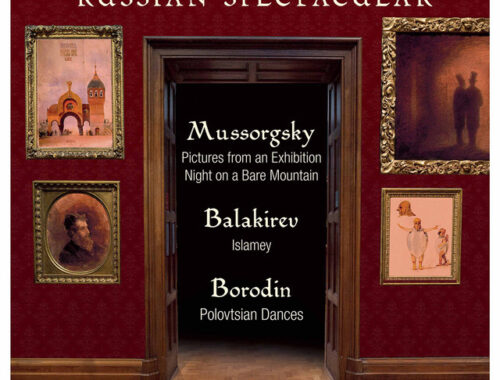

GRAMOPHONE Review: Russian Spectacular (Balakirev, Borodin & Mussorgsky) – Singapore Symphony Chorus & Orchestra/Shui

27/07/2021

A Conversation With DAME DIANA RIGG

13/11/2015