La finta giardiniera, Glyndebourne Festival Opera

The title of the opera provides the essence of Frederic Wake-Walker’s staging. Finta – pretend, fake – and giardiniera – gardener – are key elements in a show where Arcadian bliss is not even glimpsed until the counterfeit facade of 18th century manners and deceit has quite literally crumbled away. Wake-Walker and his designer Antony McDonald keep the garden of delights out of sight and out of mind throughout the long – very long – exposition of 18-year-old Mozart’s fledgling opera. Locked doors and shutters keep the air and light from airing their fading interiors. Plaster falls from the ceilings at the slightest movement, characters are frozen in highly choreographed poses or rendered limp and impassive like puppets. In Mozart’s and the director’s view they are puppets in a cruel game of elusive love and disappointment and for once it is not the director but the opera, the composer and the librettist, who gently lampoon the opera seria form with its protracted arias and anarchic ensembles where everyone noisily bemoans their lot at one and the same time. The metaphors are heavy-handed but the director’s sleight of hand is a delight. The show dances. This is a better, far better, production than the opera deserves. I’m not quite sure why Glyndebourne – apart from being a Mozart house of great repute – chose to revive it.

The title of the opera provides the essence of Frederic Wake-Walker’s staging. Finta – pretend, fake – and giardiniera – gardener – are key elements in a show where Arcadian bliss is not even glimpsed until the counterfeit facade of 18th century manners and deceit has quite literally crumbled away. Wake-Walker and his designer Antony McDonald keep the garden of delights out of sight and out of mind throughout the long – very long – exposition of 18-year-old Mozart’s fledgling opera. Locked doors and shutters keep the air and light from airing their fading interiors. Plaster falls from the ceilings at the slightest movement, characters are frozen in highly choreographed poses or rendered limp and impassive like puppets. In Mozart’s and the director’s view they are puppets in a cruel game of elusive love and disappointment and for once it is not the director but the opera, the composer and the librettist, who gently lampoon the opera seria form with its protracted arias and anarchic ensembles where everyone noisily bemoans their lot at one and the same time. The metaphors are heavy-handed but the director’s sleight of hand is a delight. The show dances. This is a better, far better, production than the opera deserves. I’m not quite sure why Glyndebourne – apart from being a Mozart house of great repute – chose to revive it.

Of course, Mozart is Mozart and throughout the opera’s unwarranted length (there are at least four false endings) we glimpse the wonder of things to come – a splendid aria for Don Anchise (Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke) where the character himself provides commentary on the darkening hue of the music – key changes, orchestration, and the like – whilst actively resisting the mounting despair. This is parody of the genre at its most sophisticated but even a Mozart of 18 years was not yet ready to carry the ambition of his ideas forward. The mature genius of Handel might be able to vary colour and sustain interest through aria upon aria but here there is a sameness and uniformity of tone that yields only to those numbers where the magic descends and the flowering of inspiration provides blooms like the celebrated aria of cooing turtle doves for Sandrina – the captivating Christiane Karg – where undulating strings freshen the stale air and we’ve suddenly a premonition of Figaro‘s Countess raising the level of enchantment. There’s also a marvelous aria for Ramiro – the mezzo trouser role beautifully taken by Rachel Frenkel – in act two where competent juvenilia is again elevated into something more.

Act two really does test one’s patience and then some and whilst Robin Ticciati’s conducting attends to the charm and elegance well enough, eliciting some lovely playing from the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, I really wondered if he could have injected more pace into act two?

Still, plenty to enjoy in the staging: the perpetual dance of courtship and confusion, the undressing metaphor where clothes are peeled away like the skin of an onion (so many layers in 18th century attire!) but desire, like the undressing, is stopped short of nakedness. I liked, too, the way the set facade becomes paper thin and also ripe for stripping in act two. It’s only a matter of time before the superstructure of this outmoded operatic form collapses before our very eyes. The issue is how much time.

You May Also Like

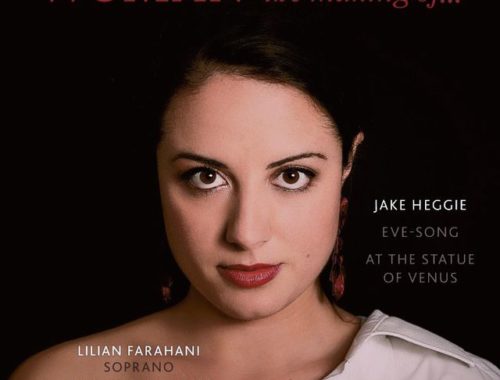

GRAMOPHONE Review: Heggie ‘Woman: the making of…’ – Lillian Farahani/Maurice Lammerts van Bueren

08/11/2019

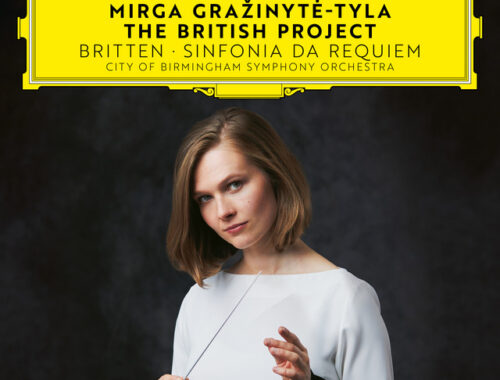

GRAMOPHONE Review: Britten Sinfonia da Requiem – City of Birmingham Symphony/Gražinytė-Tyla Orchestra

09/12/2020