Massenet “Werther”, Royal Opera House

Rolando Villazón is back. That was the overriding headline of this highly emotional revival of Massenet’s heartbreaker. The other was how and why Benoit Jacquot’s painterly staging came to be so lambasted from some quarters when it was premiered in 2004. This opera is all about keeping up appearances in direct contradiction of innermost feelings and from the moment the curtain prematurely rises to reveal Charles Edwards’ idyllic sun-kissed courtyard and Antonio Pappano’s orchestra ploughs in with terrible foreboding, you know that Jacquot has instinctively understood the inherent conflict between surface and subtext. Like the poetic imaginings of Massenet’s eponymous protagonist, what we see does not necessarily chime with what we hear and feel.

So it was a heartening night for Villazón after the trials and tribulations of his vocal problems and those ill-advised concerts of Handel and Mexican song, both of which were intended to ease him back into mainstream opera but which merely sent out the wrong signals. It’s a voice that will always need careful handling (as in no more Don Carlo), a voice of warm and vibrant character but one which lacks that essential core of resilience. Then again, what he, the singer, has in abundance is heart and soul, and in this a role which is indubitably a perfect fit for him, his vocal elegance and old-fashioned manner are both deeply touching and entirely in character with Werther, the poetic dreamer.

“Sun, flood me with your radiance”, he sings, the voice opening to its embrace, the sound melting away to rapturous effect. There is a childlike wonder to his singing which works like a charm here but one should never underestimate the vocal skill which enables him to achieve those affecting dynamic nuances, those subito piano effects achieved on the portamento. Or indeed the big-hearted intensity of feeling which finds release in the top C of act two’s thrilling climax.

Thanks to Pappano’s wonderful work with the orchestra, the lightness and poetry and surge of their playing, acts three and four build almost unbearably to the inevitable tragedy. The cool Vermeer-like beauty of Sophie Koch’s Charlotte, trapped in the confines of a loveless marriage based only on a promise made to her dying mother, conceals such heartache that by the time Jacquot’s “tracking shot” takes us through the snow to the lovers’ final reunion, the idea of life beginning at the moment of parting makes this one of opera’s most uplifting tragedies – at least when it’s done this well.

You May Also Like

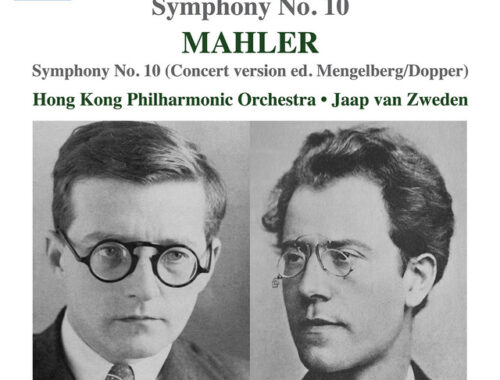

GRAMOPHONE Review: Shostakovich Symphony No 10, Mahler Symphony No 10 – Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra/van Zweden

27/02/2023

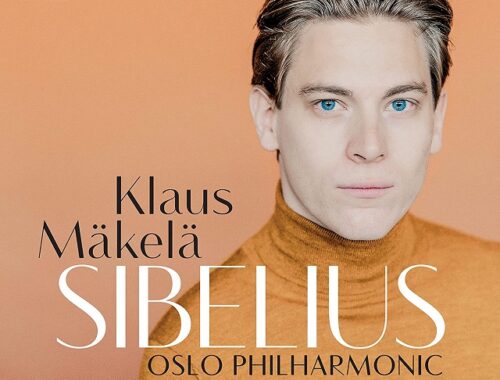

GRAMOPHONE Review: Sibelius Complete Symphonies – Oslo Philharmonic/Makelä

25/04/2022