Michael Ball: Voice of the People

The Independent

The Independent

Monday 14 April 2014

Michael Ball seems to have it all – the finest show voice of his generation, charm, good looks, swooning fans. But? In Edward Seckerson’s opinion, there are no buts.

Lloyd Webber liked it, the public adored it, and the single they made of it went to No 1 in the UK charts, selling out the show for the best part of a year before it even opened. Ball sang that top B twice nightly at the West End’s Prince of Wales Theatre (four times on matinée days). “Love Changes Everything” changed everything for him. There was a lot of dosh in that top B.

“Love Changes Everything” was a not very good song from one of Lloyd Webber’s very best scores – a subtle, elegantly fashioned chamber piece that is rarely, if ever, mentioned along with Phantom, Evita or Cats but that is a more natural expression of his lyric gifts than any of his other work. Nor was Aspects of Love a one-song role for Ball. The real challenge of playing Alex in the show was an acting challenge: the journey his character made, ageing from 18 to 34, breaking hearts along the way, not least that of an adolescent girl.

And Ball was proving a heart-breaker to his adoring public, too. His wholesome good looks appealed to teens and grannies alike. The voice could rock and croon and smooch to order. It was – and still is – a virile voice, but the breathiness in the sound was smooth and sexy, too. In very little time it had become the show voice on the West End circuit, with Ball the playboy of the West End world. And yet before Aspects, he had originated only one role in the West End: that of Marius in Les Misérables, back in 1985. Admittedly, that was a big break for him.

But in the process of cutting the show down from the four hours or so it ran before opening, he almost lost his only solo number, “Empty Chairs at Empty Tables”. In what he now recalls as a moment of madness born of youthful self-preservation, he turned to Trevor Nunn, Cameron Mackintosh et al (remember, this was only his third professional job) and petulantly announced: “No, I’m sorry, that’s not on. Cutting the song would be ridiculous. Without it, Marius has nowhere to go in the show; without it, he’s just a bit of fluff.” And Ball was not ready to be anyone’s bit of fluff. The song stayed.

He was less than a year out of the Guildford School of Acting and Dance Drama. Interestingly enough, he chose the acting rather than the music theatre course. Though he had sung for fun and “earned a bob or two busking”, he hadn’t at that point thought of his singing voice as a viable instrument. His first job out of drama school was in the Stephen Schwartz musical Godspell, in which he played the John the Baptist/ Judas roles. On opening night, when the set of double doors swung open upstage and he alone stilled the theatre with his a cappella phrase “Prepare ye the way of the Lord” (he sings it again now as if to remind himself of the moment), it felt electric, it felt right, he could feel the audience locking on to him. It was then that it hit him: this singing lark is a powerful force. You can say things that speaking alone cannot convey.

Thereafter, “it felt right” to sing. The phrase is significant. Most serious singers will tell you that unless you can feel as opposed to hear the sound you make, then you will never be a good singer. It’s about knowing from your body how you make and sustain the sound, how you place it, how it resonates, what you need to do to get this or that note. Ball only once went to a singing teacher but he had little to offer other than reassurance that he was not doing anything fundamentally wrong or reckless. The other stuff – musicality, feeling, communication – can’t be taught. Making a great sound, holding notes for a week and a half, means nothing if there is no connection to the heart. As Ball puts it: “It’s about relating the words, the music, the emotions from a personal place. If you crack on a note, it’s because you were meant to… ”

Spontaneously, we both bring up Barbara Cook’s recent London gig. At 73, her sound is still there, as distinctive as ever, but if the notes are not quite what they were, the feeling behind them has intensified. Ball once partnered Cook in the duet “People Will Say We’re in Love” from Oklahoma! in a Royal Variety Performance on the occasion of the Queen’s golden wedding anniversary. The song apparently had special significance for the royal couple, though in the line-up after the performance, Prince Philip (and Ball can do the voice to a T) made a point of asking what it was, claiming never to have heard it in his life before. So much for royal romance.

Actually, the course of Barbara Cook’s career has one clear parallel with Ball’s. Both have moved away from Broadway and West End successes to shape their careers in the much more personal arena of cabaret. Cook made one ill-advised foray back into the music-theatre limelight with the RSC’s famously disastrous musical adaptation of Carrie. Ball, on the other hand, enjoyed a critical if not commercial success with the London première of Stephen Sondheim’s Passion, which lured him back into the West End from TV, the big-earning tour dates, and best-selling albums – 11 of them to date. For all this he can thank his chart-topping single and… the 1992 Eurovision Song Contest. He came second by one vote when Cyprus gave all its votes to Ireland. Looking back, he feels that winning might well have cost him dearly; competing did not. The televised heats sent his first album soaring to the No 1 spot and sold out his first national concert tour.

Two new challenges now presented themselves: mastering the big venues and cultivating his recording technique. The difference, he says, between stage and film acting is between seeking “to rattle the ashtrays at the back of the gallery” and regarding the microphone as someone’s ear. He’s about to put both techniques to the test at London’s Donmar Warehouse, where, for the first time in years, he can reach out and touch his audience – and they him. Some hard-core fans have apparently bought tickets for every night. He could have sold out the venue 10 times over.

Ball has always thrived on the cabaret format, the challenge of juxtaposing many different kinds of song and quickly establishing an emotional world for each of them. He’s an easy communicator. His charm and his cheeky-chappy banter go down well with fans who want him to be as familiar as possible. But this time they’re in for a big surprise. He plans to take the whole experience somewhere else: no chat, no band or backing-group (just a piano), and no song he’s ever sung in public before. A real magical mystery tour to some dark and uncharted places.

That’s brave, I say. “Brave?” he says. “It’s bleedin’ stupid.”

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – December 2021

10/01/2022

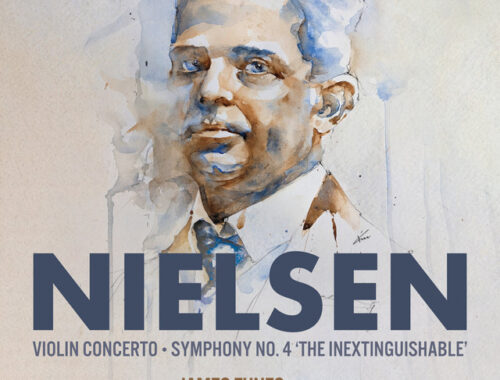

GRAMOPHONE Review: Nielsen Violin Concerto, Symphony No 4 – James Ehnes, Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra/Gardner

27/06/2023