Mozart “Don Giovanni”, English National Opera, London Coliseum (Review)

“Coming Soon”, declares the contentious poster, though even the notion that Don Giovanni would have the time or the inclination to open the packet leave alone use the condom hardly squares with the reckless dash of Mozart and Da Ponte’s narrative. No matter – at least the show itself has lost some of its dead weight and director Rufus Norris has thought better of his literal manifestations of the Don’s “magnetism”, his “electrifying” presence, and the like. What was that about anyway? My original review bent over backwards to grasp if not explain the relevance of “the Frankenstein complex” but I never got much further than the somewhat tenuous conclusion that the women in the Don’s life had somehow created a monster. Go figure. Or not.

“Coming Soon”, declares the contentious poster, though even the notion that Don Giovanni would have the time or the inclination to open the packet leave alone use the condom hardly squares with the reckless dash of Mozart and Da Ponte’s narrative. No matter – at least the show itself has lost some of its dead weight and director Rufus Norris has thought better of his literal manifestations of the Don’s “magnetism”, his “electrifying” presence, and the like. What was that about anyway? My original review bent over backwards to grasp if not explain the relevance of “the Frankenstein complex” but I never got much further than the somewhat tenuous conclusion that the women in the Don’s life had somehow created a monster. Go figure. Or not.

“Not” was Norris’ own conclusion, it seems, and his second thoughts (and credit to him for electing to unpick the mess that this show originally was) are simpler and sparer and yet still full of telling detail. The heart-shaped balloon which alone is picked out of the darkness during Edward Gardner’s trenchant, cut-to-the-bone account of the Overture is but a fickle symbol of infatuation, a kiss-me-quick trifle which cheapens rather than celebrates the notion of true love. All the women in this opera buy into it and are left with it (the balloon, that is) after the men are long gone into that dark night – a single night during which the opera speedily unfolds.

And night – as in a pitch-black void of a box – is what Norris’ designer Ian MacNeil fundamentally gives us. At the start all we see is the silhouette of a man (guess who) but other male silhouettes slowly appear on either side of him and it’s only when they emerge from shadow and some remnants of light plays on their faces that we realise that only the Don has a face and that the others all wear demon masks. How capricious it is that the Don’s own demons help get him through the night. Always there in the shadows – a sinister presence at his beck and call – they create a physical state of flux whizzing the characters through the remains of urban decay (or is it the other way around?) – tawdry rooms in bilious colours, lavatorial walls and staircases leading to upstairs rooms that don’t appear to exist. It’s ugly and it’s nightmarish and best of all it replicates, as I put it earlier, the reckless dash of the narrative.

Jeremy Sams’ cracking translation takes as many liberties as does the Don fielding more double entendres than you could shake a pitchfork at. There’s more tumescence in this text than one could ever have thought possible. Had Da Ponte still been with us he would have conceded defeat to the superiority of Sams’ “Catalogue Aria” which Leporello dispatches with the aid of spreadsheets and flow-charts. Sexual statistics on the rise, so to speak.

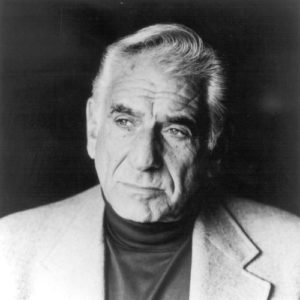

Musically, Gardner and his cast make quite a fist of Mozart’s demands. Iain Paterson’s Don is more stealthily persuasive than he was, his honeyed head-voice more irresistible. Darren Jeffrey’s beefier bass-baritone suggests an earthier alter-ego in Leporello. Ben Johnson’s wholesome singing as Don Ottavio manages to create an oasis of sincerity in “Dalla sua pace” (“When she is smiling”) with Norris, too, identifying its honesty and bringing three loving couples out of the shadows in an intimate and haunting slow dance.

And the women scorned or scornful or just plain gullible come on strong. Sarah Tynan is pretty much everything and more that you could want from a Zerlina, Katherine Broderick gives us more than just an imperious Donna Anna vocally speaking though it is in the big phrases more than the treacherous coloratura that she finds her mark. Sarah Redgwick is terrifically effective and vocally resilient as Donna Elvira – a kind of Judy Garland figure, on the edge and in search of a torch song. Well, it is dark.

A significant improvement, then, and as bleak and racy as this piece needs to be. Nice touch having the “survivors” squeeze the air from their heart-shaped balloons in the final ensemble. Disillusionment can have that effect. And Leporello trying for one last pitch with Donna Elvira shows just how much he’s learnt and who – I wonder? – he might be taking after.