Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Pappano, Cadogan Hall

Exactly one week after the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra memorably presented key players in a chamber setting, Antonio Pappano has done likewise with his Royal Opera House Orchestra – and what’s more found a common denominator. You go years without hearing the single surviving movement of Mahler’s early Piano Quartet and then, like buses, two arrive together.

Pappano himself took the piano part, a gentle pulsation in the left hand introducing a theme not Mahlerian in character at all but eminently Brahmsian – indeed a theme sounding for all the world like it was about to morph into the second subject of the D minor Piano Concerto. Brahms is very much the guiding light of this movement (never underestimate his influence) until we briefly glimpse the young and rebellious Mahler in the protracted development section. Suddenly Pappano is firing up the Lisztian double-octaves and other torrential figurations taking the music to a place in no man’s land where the home key feels briefly and provocatively remote. Most of the bonding here was between the first violin (concertmaster Vasko Vassilev) and viola (Konstantin Boyarsky). Pappano seemed “at home” among his closest colleagues.

Those colleagues have forged their way through entire cycles of Wagner’s Ring under his baton – now they mused quietly on a few of those familiar motifs with a relaxed and verdant reading of Wagner’s birthday gift to his wife Cosima: Siegfried Idyll. These truly were “forest murmurs”, a gentle stirring of bigger emotions. Two beautifully placed wind chords put the music to rest and defined the poise and tenderness of the playing.

The “big” work of the evening was Schoenberg’s chamber version of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde where the young tenor Klaus Florian Vogt looked and sounded like a fledgling Siegfried. At least he didn’t have to combat the full orchestral onslaught but rather was able to explore quality as opposed to quantity with his often very lovely open sound. The “drinking and gossiping” was charmingly addressed.

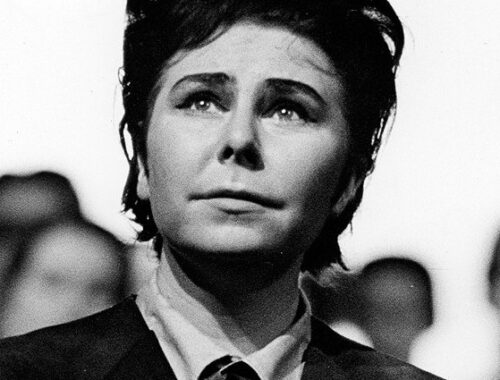

It is, I suppose, a credit to Schoenberg that one’s ear still hears the full orchestral texture whilst savouring (apart from the incongruity of the piano, that is) the delicacy and immediacy of its soloistic tinta. The playing was really very lovely – flute and oboe especially – and if one wished perhaps that Thomas Hampson had found more inwardness of sound and feeling in the final valedictions, his authority and that of his conductor was never in doubt.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – Awards Issue 2019

08/11/2019

A Conversation With VASILY PETRENKO: On Shostakovich

02/09/2010