Peter Grimes, English National Opera, London Coliseum

English National Opera’s “ownership” of Britten’s Peter Grimes was more than a little advanced by the arrival of David Alden’s thrilling staging in 2009 – and seeing it again now only confirms what I thought and felt then, that this is physically and emotionally the theatrical embodiment of the piece: a bold expressionistic reimagining of it that puts us where Grimes might be and has us seeing “the Borough” as he might see it. “Visions, fiery visions”, he speaks of, and his words confuse and threaten this closed community where belonging is conforming and where sheets of corrugated metal and sturdily boarded windows keep the sea out and the prejudices in. The Borough is as alien to Grimes as it is to us. That’s Alden’s fiery vision and it packs one hell of a punch.

English National Opera’s “ownership” of Britten’s Peter Grimes was more than a little advanced by the arrival of David Alden’s thrilling staging in 2009 – and seeing it again now only confirms what I thought and felt then, that this is physically and emotionally the theatrical embodiment of the piece: a bold expressionistic reimagining of it that puts us where Grimes might be and has us seeing “the Borough” as he might see it. “Visions, fiery visions”, he speaks of, and his words confuse and threaten this closed community where belonging is conforming and where sheets of corrugated metal and sturdily boarded windows keep the sea out and the prejudices in. The Borough is as alien to Grimes as it is to us. That’s Alden’s fiery vision and it packs one hell of a punch.

Most remarkable of all here is the physical blocking of the show, the movement of the ensemble to convey a oneness, an entity, the Borough against all outsiders. They move in concert like a shoal of malevolent fish or a sudden rip-tide. Individuals are swallowed by them or emerge waving not drowning from their midst. The great pre-storm ensemble “Now the flood tide and sea horses”, strafed by Adam Silverman’s stark and startlingly lighting – all strobe and grotesque shadow – is as physical an embodiment of what we are hearing as I have ever seen.

And what Alden and the quite remarkable ENO Chorus achieve is seamlessness between this “black mass” and the chillingly eccentric individuals within it. There’s Rebecca de Pont Davies’ dusky-voiced Auntie, landlady of “The Boar”, presiding over her pub (and the storm it seems – which she rides from her armchair) like a male impersonator of ambiguous sexual preference; her inseparable “nieces” – Rhian Lois and Mary Bevan – look like they’re ripe for grooming; there’s “fancy man” Ned Keene, apothecary and chancer, played by Leigh Melrose as all mouth and trousers; and there’s laudanum-dependent Mrs. Sedley – the glorious Felicity Palmer – who’s past ready for bedlam.

Storms like this one bring them together and when a diversionary shanty is called for (“Old Joe has Gone Fishing”) they spell out the words with their own universal hand-jiving. That symbol of “conformity” is mirrored again when the local dance – a nightmare vision of the underbelly of Little England society – morphs into a manhunt and the hand gestures grow ugly. Out come the Union Jacks and intimations of the National Front. No words necessary: the innocuous dance music now also morphs into an ugly chanting.

What I love most about this production is how elemental it feels. The scene between Iain Paterson’s marvellous Balstrode (did he lose his arm to a hungry shark?) and Stuart Skelton’s consummate Grimes is played out in the teeth of a gale, both pinned against an improvised sea wall, and the relish with which Skelton screams “And here I shall stay!” marks him out as a force of nature.

The range of what Skelton does vocally across some of the trickiest transitional writing between head and chest voices is both remarkable and beautiful. His little ariosa in the hut scene where he imagines “kindlier times” was truly bel canto for the heldentenor. Every time Ellen was recalled, the softening of his whole demeanour made the pent-up anger unthinkable. Heartbreaking.

So was Elza van den Heever’s subtly and beautifully sung Ellen Orford. What a fine instrument she possesses. She was the more affecting, too, for not playing on the sympathy but rather the strength of a principled woman. Like Skelton her vocal artistry found ways around the awkwardnesses and difficulties in the writing. Feeling always governed the shaping of the line.

Finally, Edward Gardner, who has hit some heights with this company and did so again here driving and inspiring his wonderful orchestra and chorus to the limit of their potential. I will most remember the space and silence he respected in this score and the heartstopping expansiveness of that passage enshrining Grimes’ words “What harbour shelters peace” at the end of the storm interlude. He gave it all the time in the world for reflection and in doing so dug very deep indeed into the heart of this piece.

An evening of huge accomplishment for the entire company.

You May Also Like

A Conversation With DAME JANET BAKER

25/12/2014

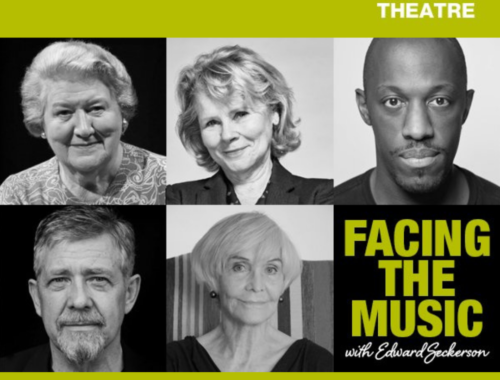

CHICHESTER FESTIVAL THEATRE at Home: FACING THE MUSIC

03/02/2021