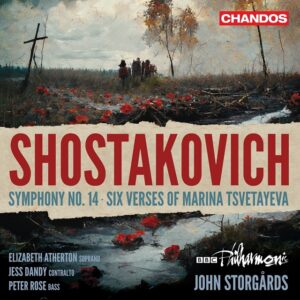

GRAMOPHONE Review: Shostakovich Symphony No 14/Six Verses of Marina Tsvetayeva – BBC Philharmonic/ Storgards

With Shostakovich’s word-setting what happens between the words is, more than with any other composer I know (with the exception of Britten to whom the 14th Symphony is dedicated), reflected in what is happening between the notes. Sometimes absolutely nothing – or rather nothing and everything. Less is definitely more. And silence is invariably deafening.

With Shostakovich’s word-setting what happens between the words is, more than with any other composer I know (with the exception of Britten to whom the 14th Symphony is dedicated), reflected in what is happening between the notes. Sometimes absolutely nothing – or rather nothing and everything. Less is definitely more. And silence is invariably deafening.

It’s that ability to make space for the words and then underline them in such a way as to make it impossible to imagine them set in any other way. The poetry of Marina Tsvetayeva revisits familiar territory – power, hardship, resistance, death – and in his choice of Six Verses Shostakovich converses once more with Hamlet and his conscience, solo viola hinting at ambiguity of being and not being. There are two settings referencing the relationship between Tsar Nicholas and Pushkin where the martial undertow is unsettling and the seemingly incongruous but vehement xylophone echoes the 14th Symphony. The bells of a new dawn are, as ever, muted in the final setting. The weight of history is all in the subtext but we hear it too in Jess Dandy’s dark and penetrating contralto which sounds, in the best sense, weighed down with it.

Listening again to the 14th Symphony the unsmiling and thick bespectacled visage of the composer, forever preserved in monochrome, does not avert his gaze. This extraordinary piece celebrates life in death. The opening poem ‘De profundis’ (Lorca) begins in a barely-audible white-out of desolation – beautifully, atmospherically captured by John Storgards’ pared-down BBC Philharmonic (just strings and percussion). But bass Peter Rose and his cloak of string basses reside in the lower depths where eerie glissandi eventually think better of reaching for the light. Rose and his partner in death, soprano Elizabeth Atherton, have plainly worked long and hard on the Russian texts, pointing up the ironies and the characterisation admirably. But there is an authentic intensity which comes directly though the sound of the words and only a native can ever really capture that completely. I grew up with the electrifying Rostropovich account with wife Galina Vishnevskaya and Mark Reshetin and with all respect to Rose and Atherton it is scarifyingly ‘other level’.

In the ‘Malaguena’, for instance, the intoxication is in the wildness and Storgards’ deliberate pacing of it robs it of stink and sweat. So too the operatic imperative and dramatic narrative of ‘Loreley’ (Apollinaire) which is writ so much larger than any conventional song and frankly needs to come off the leash more. Storgards is, though, very effective in fathoming the work’s introspection and the transfiguration in the latter stages of ‘Loreley’ is numbingly beautiful – Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk in her final moments.

So all praise to Rose for his Godunov-like authority and dignity ‘In the Sante Prison’ and Atherton for the keening memorability of her ‘Suicide’ – there is much to enjoy here – but equally once you’ve experienced the authenticity and insane intensity of Rostropovich, Vishnevskaya, and Reshetin there’s no coming back from it.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE Review: Barber A Hand of Bridge, Knoxville: Summer of 1915, Medea – Soloists, Boston Modern Orchestra Project/Rose

15/09/2021

GRAMOPHONE Review: Duruflé Requiem / Debussy Nocturnes – Kožená, Berlin Radio Choir, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin/Ticciati

08/11/2019