GRAMOPHONE: From Where I Sit – August 2020

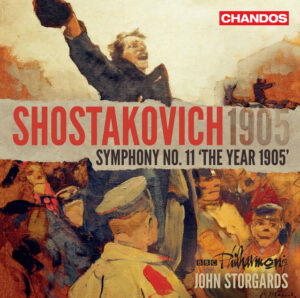

It’s always interesting getting feedback on reviews published within these pages whether there is agreement or a difference of opinion – these things are so subjective. It’s been a while, though, since a review of mine prompted the kind of endorsement that greeted my appreciation of John Storgards’ outstanding BBC Philharmonic account of Shostakovich’s Eleventh Symphony ‘The Year 1905’ in the June issue. And unusually the enthusiasm was as much directed at the work itself as at the thrilling Chandos recording. Thinking back to the live performance as last year’s Proms I can even remember my neighbour (a complete stranger) initiating a debate about the momentous clangour of bells (on loan from the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic) at the close which Storgards chose, unforgettably, to have ringing out from the gallery of the Albert Hall.

It’s always interesting getting feedback on reviews published within these pages whether there is agreement or a difference of opinion – these things are so subjective. It’s been a while, though, since a review of mine prompted the kind of endorsement that greeted my appreciation of John Storgards’ outstanding BBC Philharmonic account of Shostakovich’s Eleventh Symphony ‘The Year 1905’ in the June issue. And unusually the enthusiasm was as much directed at the work itself as at the thrilling Chandos recording. Thinking back to the live performance as last year’s Proms I can even remember my neighbour (a complete stranger) initiating a debate about the momentous clangour of bells (on loan from the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic) at the close which Storgards chose, unforgettably, to have ringing out from the gallery of the Albert Hall.

That Shostakovich speaks to people of all generations and all levels of musical appreciation is unquestionable. He is the composer (or certainly one of the composers) who invariably engages with those coming to classical music for the very first time and quite apart from the obvious – the power and immediacy of the musical language – I have other thoughts as to why. Over the years I have met some of this music’s most seasoned interpreters – from Mstislav Rostropovich to the composer’s son Maxim – and just recently I compared notes with Nicola Benedetti (who deems Shostakovich her favourite composer) on this symphony in particular. Like me it moves her more than any other in the canon – and that in itself might at first seem strange since in the immediate aftermath of its premiere it was somewhat dismissed as little more than a highly pictorial underscoring of an especially painful episode in Russian history: the failed uprising of 1905. There are still those (though fewer these days) who are damning with faint praise about it particularly when weighed against the universal respect for its predecessor, the Tenth. But in the years since Solomon Volkov’s controversial book Testimony was published we have all come to realise that this piece is about so much more than the 1905 uprising but rather about uprisings against oppression wherever and whenever they may occur.

The thematic fabric of revolutionary song is as direct as it is profound here. Consider just one of those source melodies ‘Bare Your Heads’ and its journey from brassy outrage and/or Tsarist oppression to a universal lament for the fallen in the symphony’s unforgettable cor anglais solo in the finale pitched high into the instrument so as to convey the full import of its anguish.

So often in Shostakovich there may be little or nothing on the page – and for sure those empty wastes are as potent as the thunderous climaxes – but the subtext speaks volumes. The weight of history and human endeavour and endurance is felt across the decades and centuries. Be it a solo woodwind plaint or a battery of side-drum led percussion coming upon us like a wall of sound – as in the ‘Bloody Sunday’ massacre of the Eleventh – the directness of utterance is overwhelming where lesser mortals might generate only hot air.

And those bells at the close of the Eleventh. They toll for us all. But they are at once a Tsarist coronation and an alarum of foreboding.

You May Also Like

COMPARING NOTES: Laura Pitt-Pulford in conversation

05/01/2021

GRAMOPHONE Review: MERS(S) Debussy Dukas Cras – Appassionato/Herzog

22/04/2024