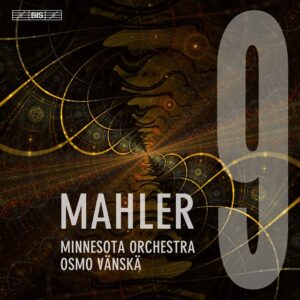

GRAMOPHONE Review: Mahler Symphony No. 9 – Minnesota Orchestra/Vanska

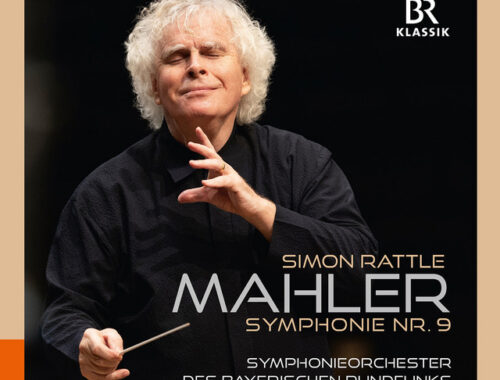

Vanska’s Mahler 9 arrives in the wake of Rattle’s recent Bayrischen Rundfunk recording – his third of the piece – and perhaps the quality most found wanting by comparison with Rattle is warmth. It’s true that this is a piece full of night terrors and deathly confrontation but Rattle gives us more of the humanity, of Mahler the man, than Vanska’s more objective reading does. Which is not to say that Vanska lacks passion – not a bit if it – just that he is perhaps more focused on all that is innovative and radical about the score.

Vanska’s Mahler 9 arrives in the wake of Rattle’s recent Bayrischen Rundfunk recording – his third of the piece – and perhaps the quality most found wanting by comparison with Rattle is warmth. It’s true that this is a piece full of night terrors and deathly confrontation but Rattle gives us more of the humanity, of Mahler the man, than Vanska’s more objective reading does. Which is not to say that Vanska lacks passion – not a bit if it – just that he is perhaps more focused on all that is innovative and radical about the score.

There is a steely resolve about Vanska’s first movement emerging from the shadows in quite forensic detail. Its ugliest colours – worming bass clarinet, stopped horns and so forth – are in sharp relief and he is particularly effective in those ‘directionless’ passages such as that which precedes the first seismic upheaval. He really opens out the tempo in these passages allowing them to find their own space, so to speak. A bleak no-man’s-land. His pedigree in the music of his countryman Sibelius stands him in good stead in that regard. There is also a sense of real panic in the climaxes, the last of them (as with Rattle) hitting a veritable wall of trombones. Thrilling. The Minnesota Orchestra’s virtuosity is self evident and the BIS engineering is superb.

But with the inner movements – Mahler’s somewhat jaundiced view of the worst aspects of country and town life – I don’t feel I’m getting all of the subtext through his characterisation, or rather lack of it. The second movement’s country dancing is very deliberate and gritty for sure but despite the lumpen tempo (generally too slow?) I’m not sure it conveys clumsiness, awkwardness, and yes charm. The ripe oom-pah tuba and bass trombone make their mark, though.

Vanska is much more in his element in the ferocious Rondo-Burleske where the trenchancy of the rhythms and razor-sharp point and counterpoint really hit home. Again though, the heartbreak of the central section culminating in the clarinet’s derisive mimicry of its tenderest theme doesn’t pull at the heart strings as it can and must.

It is after all a deathly premonition of the valedictory finale where, in Vanska’s reading, the impassioned string invocations sound too assertively ‘accented’. Some special playing, though, and the prolonged and halting fade to black is as ever heart-stopping.

So for all its excitement Vanska would not be my personal choice for a Ninth, far from it, but I can think of a number of Mahler sceptics who will be drawn to his Boulez-like objectivity.

You May Also Like

GRAMOPHONE Review: Mahler Symphony No. 9 – Bavarian Radio Sinfonieorchester/Rattle

06/01/2023

GRAMOPHONE Review: Bartók Concerto For Orchestra, Four Orchestral Pieces – Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra/Canellakis

27/06/2023